As we continue to navigate through today’s evolving healthcare landscape, the need for thoughtful innovation is at an all-time high. As oncology administrators, we are responsible for leading our teams through change, which requires engagement, buy in, and input from our front-line workers. One strategy for navigating meaningful change, which has been gaining momentum in many industries, is the process of design thinking. Although the term “design” may create the impression that this process would be best served in engineering or product design, it adds a sense of creation and innovation that is critical to the process.

Design thinking has been used in a variety of professional fields for many years; however, those in the healthcare industry have only recently begun to understand the potential benefits of this process. In an article published in 2017, Kim and colleagues detailed some of the positive experiences that hospital administrators have had with the process.1 For example, they reported that Johns Hopkins Hospital used elements of design thinking when it created a team of coaches trained in the importance of empathy in clinical settings, and a team of advocates that visit patients who are facing unusually difficult circumstances.

In an article on the design thinking process, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2018, Altman and colleagues discussed the fact that many health systems are now using the empathy-driven process and are seeing results related to improved patient experiences.2

As we will discuss, the design thinking process is largely a nonlinear sequence of working through the unknown. Although our brains naturally want to solve problems with quick, effective solutions,3 it is important that we keep an open mind and allow the process to take its course.

Throughout this article, we will continually reference the word “empathy,” which in the design thinking process signifies viewing the world through the lens of the “users.” With these users in mind, we will work back and forth through the 5 steps of the process: 1) empathize, 2) define, 3) ideate, 4) prototype, and 5) test.

Process of Design Thinking

Empathize

The first step of the process begins with an effort to understand and empathize with the users and to develop a common understanding of what the actual problem is that they are facing. In this context, the “users” may be your employees, your patients, your physicians, or anyone who this process is affecting as the “end users” of the solution. This often begins with recognizing a theme or overriding concern, such as frustrations surrounding working from home or long wait times in an outpatient clinic. Time is then taken to speak to the individuals with an open mind and an open heart. This period should be a time of learning and exploration in which open-ended questions are used to truly understand their concerns.

Define

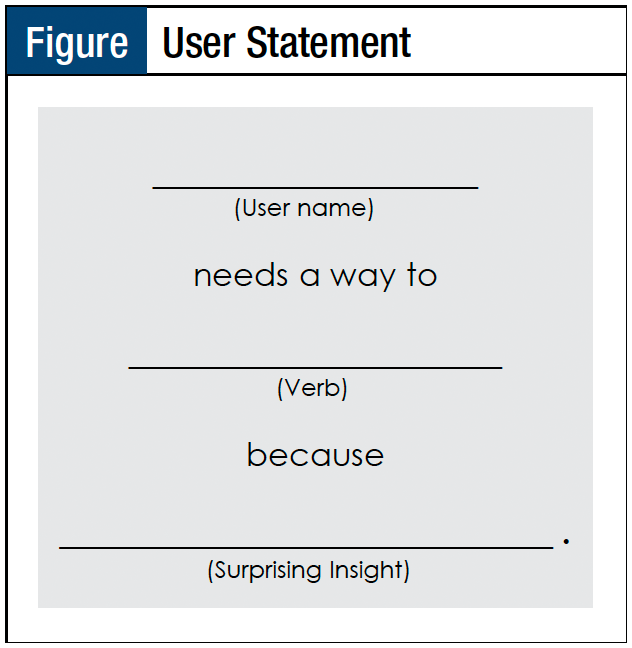

After performing your empathy “field work,” it is time to focus. As you work through this step of the process, you will ebb and flow through periods of flaring and expansion, focusing, and fine tuning. During this period of definition, you will be taking all of the feedback you have gathered during your field work to find a common problem that you will now focus on solving. It is important to ask yourself the following questions: What are my people telling me? What are the common themes that are being displayed to me? What concern is having the most impact and what problem could I solve to help those I am serving? Once you have centered on a problem, define it by portraying your users as one person, creating a user statement as shown in the Figure.4

Ideate

During this step of the process, you will again “flare” by coming up with as many solutions as possible for your user statement. This time should be exciting and fun. Whether structured as a brainstorming session, an exchange via electronic communications, or an interactive session using a physical or virtual story board (eg, a mural), there are no bad ideas and no wrong answers. After your thoughts have been recorded, you can begin the refinement process. The goal is to determine which solution will have the greatest positive impact on your users.

Although this process is one of expansion and is indeed a thought-provoking activity, it can be helpful to set boundaries during your brainstorming period, such as an established timeframe for performing the activity. This will foster a sense of understanding among group members and create an environment of teamwork from the start.

Prototype

Now that you have focused on a specific solution, it is time to build the framework of what it may look like. Whether it is a process change, a method of communication, an actual physical product, or a new build in your electronic medical record system to improve workflow, your solution will begin to take form. During this step, it is important to gain feedback regarding your prototype. This should be done quickly to help you come as close as possible to a final product.

The feedback presented during this phase can often revert your course and send you back to a previous step if you think that the solution you have chosen may not actually be beneficial to your users. This is normal. Be accepting of any feedback you receive and proceed to the next iteration of your project with consideration of what you have learned.

Test

After gaining valuable feedback during the prototype step and reforming the solution you initially imagined, it is time to test what you have developed on actual uses. Keep in mind, this is not the end. This process is iterative, and although your solution may currently be effective, the environment can change rapidly, requiring revisions. During this step, it is essential to solicit feedback from those who are using what you have developed. Check in with your users from time to time and ask questions that can further refine what you have created. It may be necessary to return to the ideation step to consider new implementations or designs that can solve their problems.

Conclusion

This article serves as a brief explanation of the design thinking process. There is much more to consider, and we encourage you to explore the process and conduct additional research to better understand how it is executed. It is important to listen to those who have already gone through the process to gain their insights. If possible, find a colleague who has had success with design thinking to mentor you.

Speaking from experience, this process can lead to many breakthroughs and valuable solutions in your practice if it is implemented with an open mind. Traverse this experience with empathy for your team, your patients, and any other “users” you may identify, and the benefits can be significant and ongoing. Good luck!

References

- Kim SH, Myers CG, Allen L. Health care providers can use design thinking to improve patient experiences. August 31, 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/08/health-care-providers-can-use-design-thinking-to-improve-patient-experiences. Accessed January 29, 2021.

- Altman M, Huang TTK, Breland JY. Design thinking in health care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180128.

- May ME. Observe first, design second: taming the traps of traditional thinking. 2012. Rotman Magazine. https://matthewemay.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Observe-First-Design-Second.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- Zaldarriaga A. Design thinking: the define stage and the point of view statement. June 21, 2016. www.tlpnyc.com/blog/define-stage. Accessed January 29, 2021.